Are museums infrastructure? -Do they facilitate flow of goods, people, or ideas and allow for their exchange over space? -Do they shape the nature of a network, the speed and direction of its movement, its temporalities, and its vulnerability to breakdown? Do museums undergird modern societies, generating the ambient environment of everyday life? If museums do not fulfil any of these, SHOULD they?

Recasting Museums as Infrastructure: Explorations in a World Cafe

by Sowparnika Balaswaminathan on 20 October 2017

Aren’t infrastructures supposed to be essential, in which case, how essential really is a museum? The World Café was a safe and reflective space to engage in free-flowing, creative, theoretical discussion by professional critical thinkers. Much like the contradictory scope of its name, the World Café was able to make the high ideals of scholarship accessible across a small table.

When the organizers of CARMAH explained the format of the World Café, what struck me the most was their reason for adopting this format. In academia, our books are very long, our talks are long too, and while our conference papers are not as long as our articles, we do try to cram in as much of our argument as we can. Or at least this has been my experience as a soon-to-finish-PhD student on the hunt for dialogue, affirmation, and a job. Can you hear me? I seem to be asking the audience. Are you sure you got everything that I want to say exactly as I mean it? This desire for a control over our discourse is understandable and understandably futile. It is rarely (if ever) possible to achieve perfection in communication, and especially so when there is not enough time for the discussion for ideas presented in talks. So at the CARMAH World Café, the focus was less on the presentation of ideas and more on the discursive possibilities of ideas at academic conferences. As the CARMAH organizers explained, this was an opportunity to emphasize exploration instead of presentation. As a host of a table, I would briefly present an underexplored theoretical intervention in museum anthropology and open the floor for discussion amongst the 3-5 participants sitting at the table. After a spirited 20-minute discussion, the participants would switch to another table to consider an entirely different intervention, and my table would receive a group of fresh discussants.

Art in places of Infrastructure: Highwire Travelers by Gordon Huether at the Raleigh-Durham International Airport

Messiness is usually verboten in museums unless they are under construction, like the Oxford University Museum Natural History in 2013

Infrastructures within Museums; Roman architecture at the British Museum, London

Part of Sou Fujimoto Architects exhibit in Cooper Hewitt’s Beauty Exhibition in 2016

The National Gallery of Art in London attracts tourists and residents, indexing many qualities that make a city cosmopolitan

The Pitt Rivers Museum is a museum of assemblages

Visitors in repose at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC

The Indo-Saracenic architectural style of the Madras Museum (Chennai) hints at its colonial roots and the infrastructural function it might have served during the British Raj as a surveying, documenting, and representing institution

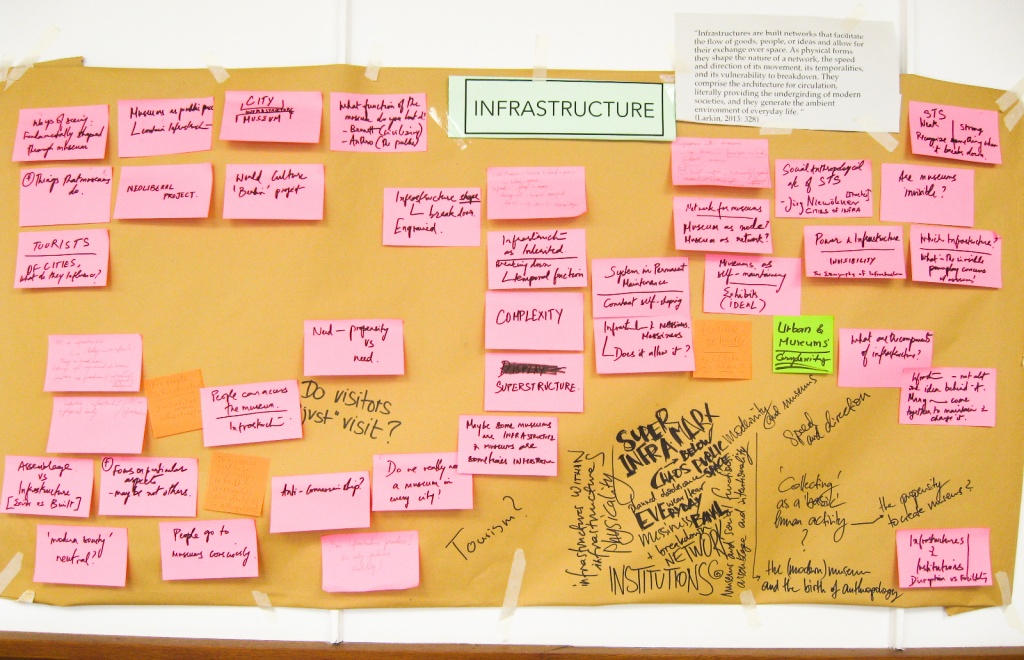

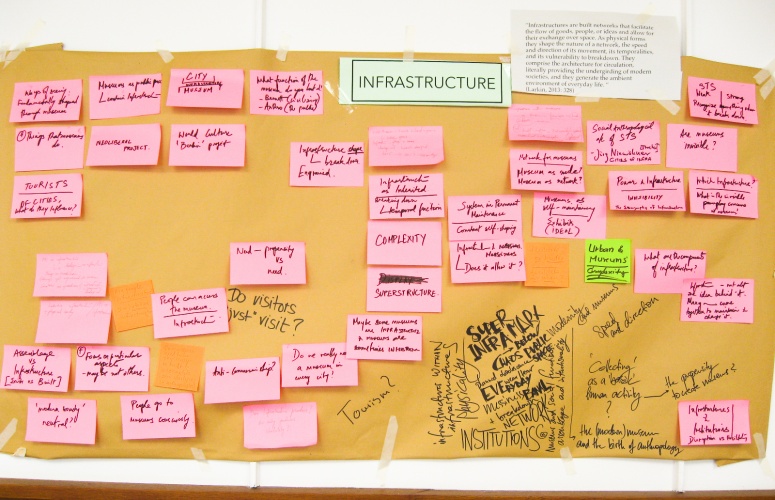

Infrastructure poster that resulted from the collaborations in the World Café

At the outset, it has to be stressed that this report of my table captures what was essentially an intellectual exercise, emphasis on the latter word. I wanted to explore the possibility of thinking of museums differently by placing them into an anthropological category that has been talked about a lot recently – infrastructure. Brian Larkin’s (2013:328) opening sentences in his review of anthropological studies of infrastructure are as follows: “Infrastructures are built networks that facilitate the flow of goods, people, or ideas and allow for their exchange over space. As physical forms they shape the nature of a network, the speed and direction of its movement, its temporalities, and its vulnerability to breakdown. They comprise the architecture for circulation, literally providing the undergirding of modern societies, and they generate the ambient environment of everyday life.“ Although what comes to mind when we think of infrastructure are material substrata, the anthropology of infrastructure imagines it as a network, a system.

Systems can facilitate or hinder ideological projects, raising the question, what are the kinds of apparatuses – development (Mains 2012), governmentality (Barry 2001), and power (Mbembe 2001) – that are revealed by infrastructure? At the same time, infrastructure is also perceived to be “invisible”, as structures that are always there, taken for granted, and made visible only when they break down (Star 1999). Larkin (2013:336) disagrees, arguing that infrastructures are metapragmatic objects, meaning they are “signs of themselves”, circulating in established ways to do a particular work. Born out of an Enlightenment idea of what became “the modern”, infrastructure is always geared towards the future and progress. Tied to this are some affective correlates such as fantasy and desire.

Because of these characteristics, it is usually the fundamental aspects of life such as water (Anand 2012), energy (Von Schnitzler 2013), or roads (Harvey and Knox 2015) that are considered. Are museums fundamental to life as we know it? Should they be?

Museums have been markers of progress, power, cosmopolitanism, benign urbanity, historicity and tradition, and modernity. Every city and town, at least in the Western hemisphere usually has a museum. Every visitor, school child, or even an adult with leisure visits the museum as a thing you just do. Critiques of museums have tasked them with being colonialist, static, elitist, corporate and neoliberal, and facile with difficult knowledge. The separation of museum operation from museum critique also has consequences for how they are perceived and portrayed. The World Café roundtable was an attempt to re-categorize museums to see if anything valuable could be obtained out of it. Are museums infrastructure? In terms of critique and operation, should they be considered under the category of infrastructure? What happens when we inquire into the museum and its practices by assuming that it is part of the infrastructure of a nation-state, a society, a culture, or even a city? How would this change the way we think about museums and the way the museum thinks about what it is supposed to do?

Thus, I posed a series of questions to the participants in order to generate discussion, primarily by going back to Larkin’s definition:

Are museums infrastructure?

- Do they facilitate flow of goods, people, or ideas and allow for their exchange over space?

- Do they shape the nature of a network, the speed and direction of its movement, its temporalities, and its vulnerability to breakdown?

- Do museums undergird modern societies, generating the ambient environment of everyday life?

If museums do not fulfil any of these, SHOULD they?

Larkin’s definition of infrastructure notes that being “built” is an important criterion for infrastructure. A happenstance set of elements cannot unintentionally facilitate circulation. A network takes effort. What about inheritance, a participant asked. Museums are often made of inherited artifacts, some donated, but many others plundered and procured through colonial enterprises. Can museums be called infrastructure then? One participant noted that while a collection might have been inherited, there was still an intention to collect and assemble. If infrastructure is supposed to maintain a system, museums can be seen as an element of colonial infrastructure – maintaining symbols of power, and positioning members of various societies into a world hierarchy even in a postcolonial society. In this context, the relationship between museums and anthropology was striking to the participants. American anthropology was born out of the extensive collecting of Native American artifacts and narratives by American explorers much of which eventually ended up at the Smithsonian. Thus, the Smithsonian could be seen as facilitating the discipline of anthropology, that is, the infrastructure for American anthropology. Considering that museums also shape the ways in which the “others” are perceived by society, their facilitation of anthropology (which is the discipline in which an anthropologist attempts to understand difference or similitude through personal interaction with other people and translates what they understand as the perspectives of “others”) is but a more specific rendering of their larger practice. This raised the question, however, if museums can be considered monolithic in their practice, and if we were not being traditionalist in ascribing such a function to the museums of the present. Participants wondered then how the museum as an entity was itself made of infrastructures – the physical constructed spaces, the human organizers, the bureaucratic rules, ethical codes, managed collections, not to mention the very important financial undergirding. So while the museum could be an infrastructure, it is also made of infrastructures, and analyzing those components is important for determining what role a museum is supposed to play.

One of the roles that museums appear to have in the world today is as a symbol of cosmopolitanism or liberal ethos. Tony Bennett’s (1995) argument was that museums historically used to contain a civilizing function through which the common masses could be educated into being ideal citizens of an urban centre. While such aspects of the museum have been deconstructed and critiqued, and there is a more thoughtful operative practice in play nowadays, the very presence of a museum in a city signals values beyond the cataloguing of history – museums index “culture”. Who goes to museums and who can afford to? While tourists used to and perhaps continue to be the main draw for larger museums, large and smaller institutions have branched out to acquire local patrons who are expected to support it with bodies if not money. These are the “Friends” of a museum and their support of the institution is returned with ease of entry for repeat visits and special considerations for events. In short, the present day museums situated in urban centres are building and facilitating communities composed of people who occupy particular social positions. In this sense, could museums of this sort be considered the infrastructure for cultural capital? Some participants expressed dissent and argued that this line of thought makes it seem as if every city (administration) thinks that it is essential to have a museum and that is not so. Furthermore, do we really need a museum in every city, asked a scholar. Aren’t infrastructures supposed to be essential, in which case, how essential really is a museum?

This line of thought of the essentiality of the museum was also discussed by a group of participants who explored the Marxist notions of substructure and superstructure, wondering under which category infrastructure would fall. Materially, infrastructures are supposed to support the circulation of materials, peoples, things, and ideas, so one participant wondered if infrastructure fit under the substructure. However, for Marx, substructure referred to the relations and forces that facilitated production, and these were the social practices that could be generally conceived of under economics. Shouldn’t infrastructure have to come AFTER the establishment of the substructure as Marx conceived of it? Would museums fall under the category of “superstructure”, which includes all the other aspects of society such as politics, culture, and so on? Yet, several scholars have argued that separating substructure and superstructure is counterintuitive since they are so closely tied together. To answer the question of whether museums are essential might not be as important as to acknowledge that what is “essential” depends on the circumstances of the environment, and also, it is not always the essential that becomes prioritized.

The dialogue that proceeded was rich, diverse, generative, and interrogative. While some participants wanted to deconstruct the definition of infrastructures themselves, others questioned the position of the museum in society. As an exploratory venture, the topics came out of nowhere and sometimes returned from earlier discussions. Arguments meandered and when it seemed like we were close to exploding a concept, it slipped away. Sometimes it did not. What follows is an account of the discussion that occurred across three sets of participants numbering from two to five in each round. Keeping in the spirit of exploration, there is no unified question or argument in this report, just discussion.

Questioning what makes something infrastructure, a participant wondered if an assemblage (such as a museum collection) can be considered similar to infrastructure. After all, an infrastructure is considered to be a network, a coming together of multiple parts. A museum facilitates the coming together of multiple artifacts, and the term, “assemblage” has frequently been used in association with collections. So what makes an infrastructure not an assemblage? Firstly, it was discussed that an assemblage indicates a level of separateness to the objects such that while they might be together, their individuality has a notable significance. Infrastructure, on the other hand, points to an entity in which the connection is crucial. Secondly, an assemblage could be something that exists, while an infrastructure requires conscious building. Intentionality is paramount in the existence of infrastructure while with an assemblage, it could go either way.

One participant, going back to the discussion on Marxist ideologies of structure, asked if infrastructure produced anything at all and another answered that it seems to produce stability. The Science and Technology Studies background from which the category of “infrastructure” has spread to other disciplines describes it as systems in permanent maintenance. In that sense, infrastructure is a self-shaping mechanism that maintains status quo in the face of changing circumstances. Can infrastructure allow for messiness? At this point, a participant asked for a clarification: do we really mean messiness or complexity? It is important to acknowledge that infrastructure, while it might be in the service of maintaining the status quo, is not bereft of political considerations either. The places where infrastructure works well, where it doesn’t, who gets access to it, and what it facilitates are all laden with social meanings that index power. Thus, while ideally infrastructure is supposed to make things simpler, its existence and operation consist of and promote complexity.

How do museums fit here then? Are museums systems in constant maintenance? There is certainly an attempt by certain museums to adopt the white cube model literally and ideologically, and to stand as neutral spaces that host the subjectivities of others. However, critical museology has also forced museum scholars and practitioners to acknowledge the political weight of the museum, not to mention the economic forces behind it. More and more museums have actively engaged with political issues and made their subject position clear. Museums, when considered as infrastructure then can be seen as facilitating complexity – diverse meanings, nuanced dialogues, and disenfranchised subjectivities. Infrastructure, several participants concluded appears to signal complexity, and aren’t museums arbiters of complexity too?

At the end of the World Café, I was exhausted, as I am sure were the participants. While I had to merely host one topic, the participants battled three each. I use the term “battle” here lightly, but it should be noted that as scholars in academia, it was difficult to not immediately engage in critique when the discussion started. As an exploratory exercise, the World Café featured ideas that were nascent in their ideological evolution and the tables hosts were bearers of questions, more than arguments or answers. Thus, whenever a discussion became oriented towards critiquing a topic, we had to remind ourselves that this was the space for creative excesses where we could cultivate and fertilize an idea. Critique could wait just a little. Ultimately, what made the World Café valuable was the generosity of the participants and the organizers. Scholarship is supposed to nurture critical knowledge, but too often we focus on the former to the detriment of the generative potential of the latter. This is not to say that critique is not generative, but when critique asphyxiates creativity, it can become a problem. The World Café was a safe and reflective space to engage in free-flowing, creative, theoretical discussion by professional critical thinkers. Much like the contradictory scope of its name, the World Café was able to make the high ideals of scholarship accessible across a small table.

All images by the author.

Sowparnika Balaswaminathan is a PhD candidate in Anthropology at UC San Diego. She studies ethnographic & art museums, South Asian artisans, discourse, and ethics. She has taught anthropology, world history and argumentative writing and is currently an Editorial Assistant for Latin American Antiquity.