Why do Germans insist on saving despite having had their savings wiped away by wars, economic crises and hyperinflation, and despite seeing the value of their savings eroded by inflation and low interest rates? That’s the puzzle that Saving – History of a German Virtue, the new special exhibition at the Deutsches Historisches Museum in cooperation with Berliner Sparkasse, sets out to solve. The question is asked against the backdrop of mounting criticism against Germany for insisting on current-account surpluses. Restraining private and public expenditure at home to buttress its export-led economic growth at the expense of debt and deficits in the Eurozone peripheries has turned Germany into the global economy’s “problem” – as a recent cover of The Economist announces. The evasive and self-congratulatory answer that the exhibition serves up is that, well, what can you do? Saving, for Germans, is a deeply ingrained virtue and cultural trademark: “an entrenched custom rather than just an economic strategy,” in the words of the exhibition’s head curator Robert Muschalla (Connolly 2018).

Virtue out of Necessity: An Exhibition on Saving in Germany

by Hadas Weiss on 30 April 2018

There’s another puzzle hidden away among the artifacts to which the exhibition never attends. Statistics on saving trends in Germany displayed on a print board somewhere toward the end reveal that 40 percent of Germans have no savings at all. What kind of culture is it that is not reflected in the habits of nearly half of the people to whom it ostensibly applies? No culture at all, of course, unless culture, mentality, virtue or even “obsession,” to use the term favored by reporters (Buck 2018; Connolly 2018), are just another word for ideologically backed and unevenly applied economic necessity and interest.

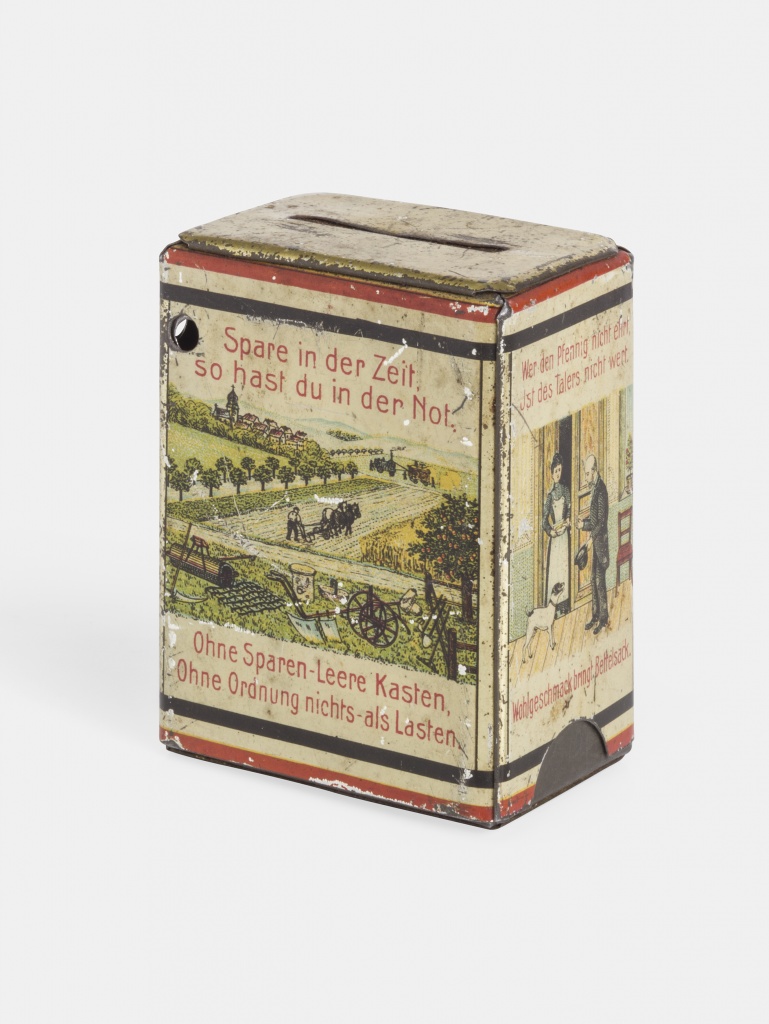

The exhibition does not shy away from addressing the political willfulness at the historical origins of saving. Since the 1778 foundation of the world’s first savings bank in Hamburg, Germany’s poor have been responsibilized avant la lettre, taught that they must provide for themselves and that if they fail to do so, their poverty is their own fault. Saving was promoted alongside thrift and hard work as a means of reducing their demands on the public purse. Behold the perfusion of household piggybanks and moneyboxes on display, stretching far back into history. “Save now to have money upon emergency” is one of the mottos etched on them, along with: “If you have nothing, you will be a burden”.

Home money box with mottos and illustrations, around 1900

Home money box with mottos and illustrations, around 1900

Nineteenth-century industrialization saw the mushrooming of savings banks across the country (an interactive map of Germany shows electric bulbs, each representing a savings bank, lighting up the entire surface as the years go by). These were primarily initiatives by local administration, a means of collecting capital to fill up treasuries and finance the construction of roads, electricity and gas works, as well as schools, theatres and public parks. True to their purpose, savings banks were established right on the ground floor of town halls. The collection of the population’s savings to finance public and political expenditures would be stretched to its logical conclusion with the mass issuance of war bonds in return for these savings during the First World War (and this is the only point in the exhibition at which comparisons are made to other countries, and specifically their wartime financing) and in the Nazi financing of armament in preparation for the Second World War.

Beyond reducing pressure on the public purse and financing public works and wars, saving was also promoted as a way of staving off revolution by chaining workers to capital. As workers’ movements gathered steam, politicians figured out that workers who have something saved up also have something to lose and would therefore not be so quick to take to the streets. I was pleasantly surprised to see an image of Karl Marx, as if addressing an impoverished proletariat, with a quotation from Capital stating that thrift is a cardinal virtue of capitalism. And with this virtue, capitalism won the day: by the beginning of the twentieth century, over a quarter of the population already had a savings account – hence something to lose – and revolutionary ferment had been defused.

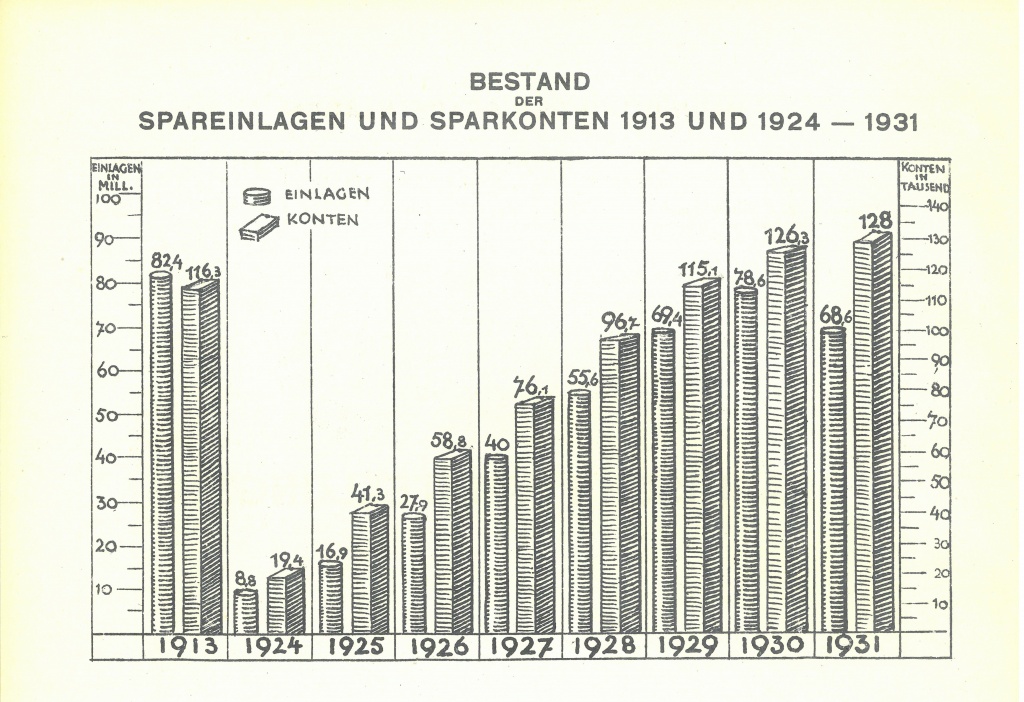

It was at this point that I interrupted our pleasant guide, who kept talking about these principles of saving as things of the past, to suggest that they might continue to hold today. “Of course”, he indulged me, but it was a foreshadowing of things to come. Account books from the years before and after the post-WWI hyperinflation demonstrated that in less than a decade after having seen their savings disappear, savings rates among Germans recovered their post-inflation levels – a trend whose recurrence set the stage for the notion that saving had morphed from diffident compliance to tenacious virtue. Reinforcing the supposed economic irrationality of this virtue, the artifacts to follow represented the anti-Semitic propaganda of saving as a mark of German-ness, a morally upright antidote to the greediness of “Jewish finance capital” which makes money grow without contributing to production.

Savings deposits and savings accounts of Hanover City Savings Bank from the business report 1931

Savings deposits and savings accounts of Hanover City Savings Bank from the business report, 1931

Gestures at political economy came to a screeching halt after that. What followed next was wall after wall adorned with cool advertising posters in which Germans were encouraged to save for more benign and pragmatic reasons. In postwar East Germany, saving was tied to the reconstructing of homes in the war-ravished country. In West Germany, it was tied to rising consumerism. Joining the ubiquitous images of families saving for a rainy day, more cheerful posters with expensive household items and pastimes now within reach announced: “saving is the opposite of stinginess”. Other posters represented saving as natural, associated with industrious bees and with prudent squirrels storing away nuts for the winter as well as with peasants sowing and harvesting seed. My favorite were posters that linked saving with women’s homemaking skills, epitomized by the balancing of a family budget; a wisdom bestowed from mother to daughter. Posters and artifacts also depicted programs like school savings banks that got schoolchildren into the habit from a young age. The items on display implied not only the self-evidence of saving – as if the rainy day would naturally be weathered, the fruits of one’s labor enjoyed and the family secured by these savings – but also the understanding that the visuals reflected back to any man or woman who had grown up in Germany what they have long since learned and internalized.

Fatal error: Uncaught DivisionByZeroError: Division by zero in /var/www/html/wp-content/themes/carmah/elements/image_lightbox.php:6 Stack trace: #0 /var/www/html/wp-includes/template.php(732): require() #1 /var/www/html/wp-includes/template.php(676): load_template('/var/www/html/w...', false, Array) #2 /var/www/html/wp-includes/general-template.php(204): locate_template(Array, true, false, Array) #3 /var/www/html/wp-content/themes/carmah/elements/flexible_content_loop.php(37): get_template_part('elements/image_...') #4 /var/www/html/wp-includes/template.php(732): require('/var/www/html/w...') #5 /var/www/html/wp-includes/template.php(676): load_template('/var/www/html/w...', false, Array) #6 /var/www/html/wp-includes/general-template.php(204): locate_template(Array, true, false, Array) #7 /var/www/html/wp-content/themes/carmah/single-reflections.php(50): get_template_part('elements/flexib...') #8 /var/www/html/wp-includes/template-loader.php(106): include('/var/www/html/w...') #9 /var/www/html/wp-blog-header.php(19): require_once('/var/www/html/w...') #10 /var/www/html/index.php(17): require('/var/www/html/w...') #11 {main} thrown in /var/www/html/wp-content/themes/carmah/elements/image_lightbox.php on line 6