The point of departure for Nanette Snoep was twofold when she arrived in the Grassi Museum für Völkerkunde Leipzig, of which she became director in 2015. First, there was the permanent exhibition, which for her “unites all the problems that are associated with ethnographic museums (…). It is the place to visit if you want to understand what goes wrong. It’s a concentration of errors, there is everything! The idea of atemporality, the organisation by regions… everything is here! It’s like a little island.” Second, right wing movements such as Legida in Leipzig and Pegida in Dresden, and also the newly established party Alternative für Deutschland (Alternative f or Germany, AfD), have steadily gained support in Saxony, in the context of, and in reaction to, Merkel’s welcoming gesture towards refugees. Paradoxically, both in the museum and on Leipzig’s streets, questions of cultural difference and the construction of the Self and the Other are at the centre of debate.

As a reaction to those contexts, Snoep developed the concept of Grassi invites to rapidly open up the museum to multiple voices. She aspires to transform the museum to an institution that can be reactive, to deal with this delicate political context from within an institution that has been constitutive of the definition a certain “us” and an opposing “other”. In her previous post at the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris as the Chief Curator of the Historical Collections,she developed an expertise in colonial history and the politics of representation, with a regional focus on Africa, in exhibitions such as “Exhibitions – L’invention du sauvage” (“Human Zoos – the Invention of the Savage”) (2011-2012) or “Les Maîtres du Desordre” (2012).

With Grassi invites, Snoep wants to “push the idea of interdisciplinarity to its extreme”, initiating different kinds of collaborations – with researchers, artists, representatives of local communities. Her work is experimental not only because of its interdisciplinarity but because the limited budget forces her to compromise. “An exhibition’s budget here is a showcase’s budget at Quai Branly!” – a situation that she describes as limiting and enabling at the same time. “You are able to do quite experimental things when you can say: ‘Well, this was only 20 000 Euros.’ With a million, it’s more difficult! The more expensive it gets, the more censorship there is.”

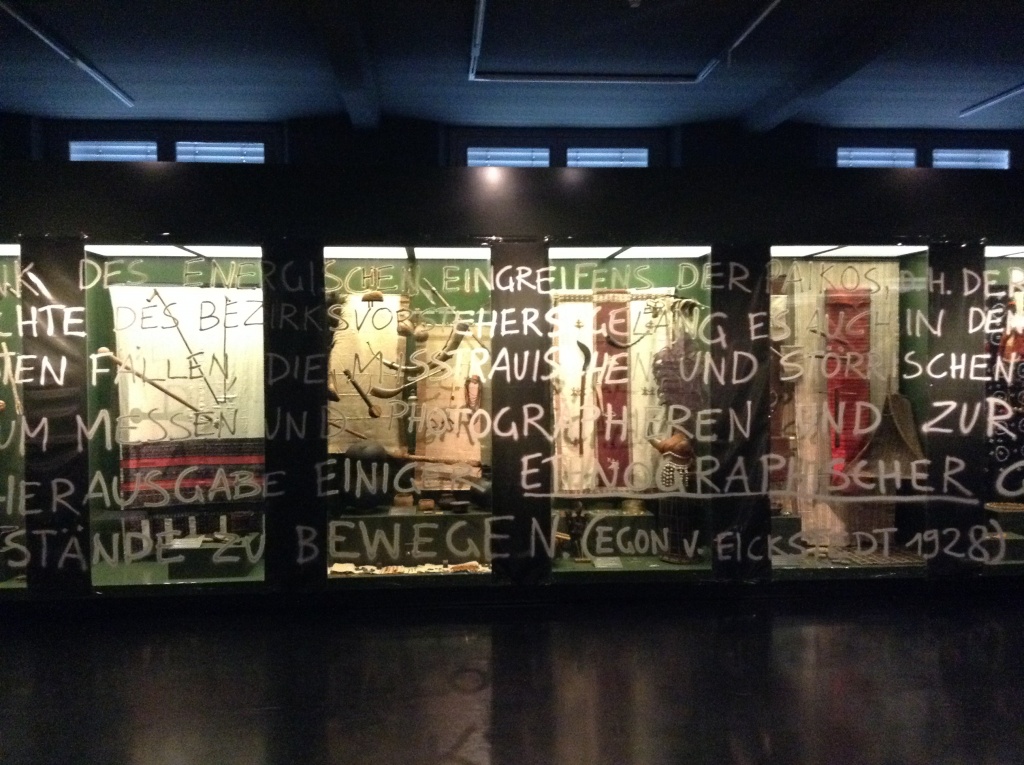

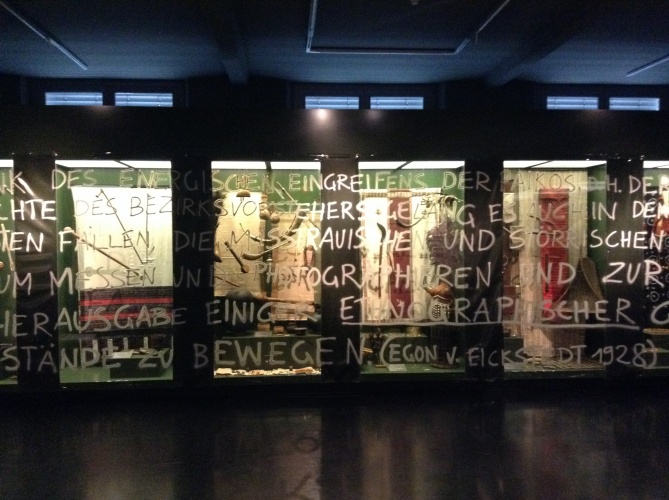

Snoep’s first initiative “Grassi invites #1” – “fremd” was on display from January to May 2016. Realized by a curatorial team from the Hochschule für Grafik und Buchkunst (HGB) in Leipzig, the works of 27 art students spanned over two floors. The students were “invited” to question modes of (re-)presentation in ethnographic museums and their effects. The only rule being, Snoep recalls, was “Don’t burn down the house and don’t let the dogs out!”. They intervened in the permanent exhibition with site-specific works and worked with the temporary exhibition space, a more neutral white cube.

The reactions to the exhibition have been polarised. The exhibition gained national attention through its appearance in “tagesschau”, a national public television news programme. In Leipzig itself, it has triggered debates inside the museum’s walls, but also on a general museum-wide and political level. Letters of complaint have been sent to Saxony’s museums’ directory. “It’s true that this exhibition is very costly for me,“ says Snoep. “At the same time, if this exhibition is considered political and polemic, well, it might be a little exhausting for its director, but I tell myself that I need to go through it. If you want multiperspectivity, if you want a place of discussion and conflict, you need to bring people in.”

This text tries to grasp a part of the diversity of voices and arguments that have been expressed concerning the exhibition. The following images of the exhibition are accompanied by comments. All the comments by visitors have been translated from German.

Would [this type of critical exhibition] be acceptable in other types of museums? (…) Once again, it is objects of other cultures which are used to deal with our problems concerning colonial times. But one does not deal with those problems inside our halls of native icons, but instead with the objects once referred to as “Primitive”, not long ago. The discourse on ‘post-colonialism’ becomes the discourse of colonialism, because methods of the colonial era and ideologically motivated destruction are applied here, obviously with no concern. It is symptomatic that the controversial installations take place exclusively concerning cultures that were formerly called “primitive”. A confrontation with the ideologically charged “High Culture”, as defined amongst others by Alexander von Humboldt, does not take place.(…)They [the students] can be sure of themselves, as long as the deconstruction of the scientific-artistic installation achieves the opposite of their iconoclastic intentions, namely the revaluation of ethnographic representation.

Claus Deimel, former director of the museum

(Extracts from Claus Deimel 2016: ”Wer den Wind sät. Rufe aus der „letzten bildungsbürgerlichen Bastion rassistischen Denkens“, Paideuma 62).

I think the intervention is necessary and so far successful. However, the language in the booklet is too academic , muddle-headed, incomprehensible. The information thus certainly remains inaccessible to many people , which is a shame. It would be nice also to integrate the intervention directly in the exhibition, for example, with panels.

01.03.2016 [ no signature]

Too bad we only understand half of the exhibition? We don’t understand the temporary exhibition. Anthropology (Völkerkunde) is very interesting to us.

Family Gönur, 7.2.2016

The guestbook always seems to be one of the most interesting ethnographic aspects that we can find in such museums. The exhibition “fremd” takes a critical journey through the history of anthropology, but stay itself a stereotype. Still, it is an enrichment for the museum and the transformation and understanding of anthropology. I will come back at the exhibition’s last day and will read further comments in the guestbook.

02.03.2016, DM

‚FREMD’ – very important and successful intervention in this exhibition! Please continue with the reflection! For the first time in a long time a reason to come here again. The way the exhibition used to be, it was hardly tolerable (stereotype, simplifying, triviliazing colonial history)

30.03.2016, S. Brehn

The exhibition ‘Fremd’ appears like a continuation of colonisation, occupying space und destroying, without showing any respect.

One can deal with colonisation with well researched texts, photos, audio plays….in an exhibition in the room for temporary exhibitions.

2.3.16 unreadable signature

Should an intervention largely consist in bashing the existing exhibition? Is that showing more respect to the people and cultures on display? Or does it humiliate them a second time? Presenting them first and foremost as victims of anthropologists and modern European museums. Is Fremd taking away the agency from people, from whom it has already been removed once?

It was still an exhibition with voices of the strangers, and not of the ones on display. For me it seemed like the art students loaded their critic on top of the existing exhibition, critic that is very much needed there but not adequate. I left the exhibition knowing more about its problematic colonial heritage, but missing knowing more about the actual life of the people whose items are on display. Maybe Grassi should sent an invitation to them as well?

Rikke Gram, CARMAH, June 2016

Museum observation – Grassi Museum, 24 April 2016

According to an introducing description that Sharon kindly translated, the museum apparently have a strong concern about post-colonial critics and attempts to go beyond and do exhibiting post-colonially in several ways. This intention and effort also has been stated clearly in the museum director’s interview and can be seen in the content of exhibitions that I very appreciated and look forward to the next phase of positive changing.

Through a short time visit and lack of info, I’m actually wondering with several things and thinking about some problematic issues relating to museum exhibitions that may be useful to make note and share with you all.

Overall, this museum covers and preserves a huge number and various kinds of cultural artefacts and reflecting quite well that how cultural diversities and differences around the world look like – at least at the physical appearances and selective areas! These collections made the museum has great potentials to do assemblage and connect the museum and collections with so many relating things – objects, persons, communities, places, stories, etc., referring to ideas of the actor-network theory, relational and dialogical museum that Grassi Museum also concerned.

In so far, I have seen a museum concerning with post-colonial criticism but not yet a post-colonial museum that practically doing well in creative or constructive ways.

The first problematic issue would be mentioned is about classifications of cultures and exhibiting material things as a part of cultural units/ containers appearing only cloths, tools, daily objects, … but missing persons and without voices or different perspectives, stories, memories, etc…

The second issue would be concerned for ethnographic museums in general is about the colonial gaze and dehumanized presentations – such as portraits through the imperial eyes or scientific measuring scales, naked photographs of indigenous people. These reproduced materials would be required more awareness even in the books or exhibitions that aiming to criticise colonialism or do post-colonising the museums. This point is also linked with an intervention that mentioning about the human zoos.

Stereotype, homogeneity, and juxtaposition is another set of problematic issues which I’m thinking about since seeing the Southeast Asian section that Thailand is a part of the exhibition. For example, in a case, there are several potteries and baskets from different regional areas of the country which possibly relating to quite different cultures have been exhibited together as a homogenous presentation of a larger scale of the geographical area – e.g. Thailand, Southeast Asia.

Siriporn Srisinurai, CARMAH, April 2016

I really liked the idea of the fremd exhibition to invite students from fields other than anthropology. Projects like this can function as catalyst: They allow the people behind the scenes to look at an exhibition throught other people’s lenses, to remind them of their responsibilities when working with these collections and they can help to approach other groups of museum users by experimenting with new formats. I thus was curious to see the students’ installations in the fremd exhibition. And while some of them might have profited from collaborating with professional interpretors to help decode the White Cube, I found most of them interesting to explore as they interrupted my strolling through the exhibition and asked good questions.

At the same time, however, I felt some kind of discomfort with the fact that issues that fundamentally question the role of ethnographic museums, especially its entanglement with past brutal colonial practices, had been left to be brought up by students. Instead of the dialogue that I had expected it seemed as if the curators themselves where invisible or had stepped back from getting involved in that dialogue. As they are the ones who usually make meaning out of objects, i was wondering how they approach the issue of the postcolonial and whether and how they embed decolonizing practices.

Christine Gerbich, CARMAH

fremd puts so many of the critiques of the classical, problematic, ethnographic museum put into practice. It is impressive just how many varied interventions are made. The Grassi permanent exhibition offered up a lot of rich material for such interventions; and the students covered a lot of critical approaches to the ethnographic museum and presumably learned a lot in doing so.

There are always risks with these kinds of experiments but that isn’t a case for not doing them, and provoking debate is worthwhile. Researchers like us and also those involved in museums – not just ethnographic ones – need to attend to such experiments and ideally also to do some kind of visitor research, to understand better what works and how, and what does not. There is undoubtedly room for developing a new level of critical debate that goes beyond the existing critiques, which sometimes feel rather obvious and even a bit tired by now – though maybe that is only for audiences like us, who already know the critiques.

I am, though, left with the question of how it is best to go on. Where can such museums go more productively in future? It is undoubtedly really difficult. Looking at the museum itself – drawing on institutional critique, interrogating forms of representation and so forth – remains important and can, I think, be done in more inventive ways. But this can’t be all that museums do. Personally, I would love to mix museums up, to work in ways that cross over the traditional boundaries between, say, museums or art, ethnography, history and so forth. The Humboldt Forum might have been an opportunity to do this – to not reproduce the existing museum categories, that is, to not think in terms of ‘let’s put the Ethnological Museum here, the Museum of Asian Art there’ but instead to cut across these and create something new. That could have been truly radical – and maybe brilliant. Maybe somebody else, some mainstream place, will do it somewhere else one day – I hope so.

Sharon Macdonald, CARMAH, June 2016

Image credits: all rights GRASSI Museum für Völkerkunde zu Leipzig

Image of visitor book by the author

Margareta von Oswald is a researcher in the Making Differences project at CARMAH. In her research on the restructuring processes of ethnological museums in Europe, she focuses on contemporary negotiations of contested colonial legacies in the present, with her main case study being Berlin’s Ethnological Museum.